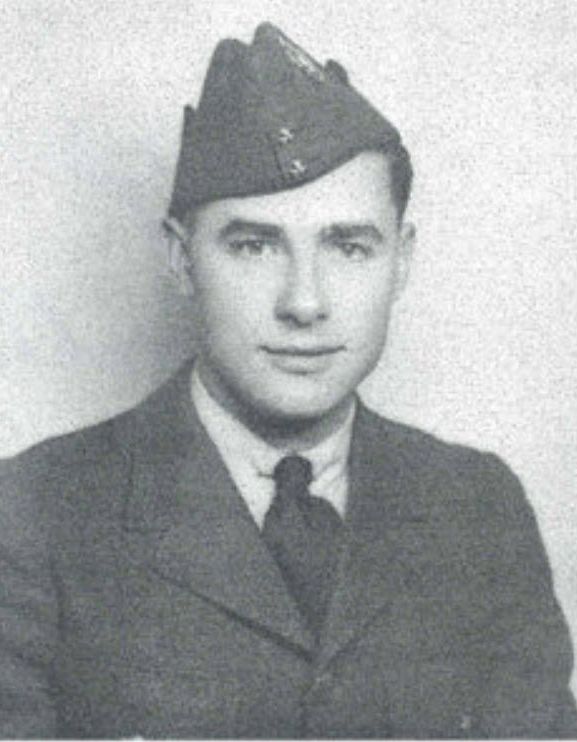

1939-Sep-14 | Warrant Officer James Doan and Corporal James Rennie | RCAF 8 (GP) Squadron

Canada’s military was small and equipped with outdated gear. But when war seemed inevitable, they were determined to be ready. The Royal Canadian Air Force prepared an Ottawa-based squadron for anti-submarine patrols from Sydney, Nova Scotia. They planned to use the Northrop Delta, an aircraft better suited for survey work than maritime patrol. It was fitted with floats to land on water, though this feature proved useful for only two months before the aircraft was withdrawn.

By late August 1939, preparations were complete for the squadron to move east.

Warrant Officer James Doan of Vancouver had been in the RCAF for twelve years. He started as a mechanic but quickly became a pilot, earning his wings in 1930. His record described him as an exceptional mechanic, but he seized the chance to fly. By 1939, he had experience with most aircraft in the RCAF inventory.

Doan was one of six pilots from 8 (General Purpose) Squadron who would fly across Canada to form 8 (Bomber Reconnaissance) Squadron on the Atlantic coast. The journey was straightforward—about six hours—from Ottawa over Quebec’s Eastern Townships, then across Maine and New Brunswick to a refueling stop in Shediac, NB. From there, a short flight would bring them to Sydney, Cape Breton, for their mission to search for enemy submarines.

Doan’s passenger was Corporal David Rennie of Ottawa, a talented engine mechanic. He had only been in the air force for a couple of years but had earned medals for proficiency in technical school.

The six aircraft departed early in the morning, flying in loose formation just 3,000 feet above the ground. Their presence was likely noticed, as aircraft were rare sights in the sky.

While flying over Maine, Doan’s plane developed engine trouble. He searched for a landing spot and safely set down on Salmon Stream Lake. Without radio communication, another pilot, Flight Sergeant William Pate, landed alongside him. The four airmen inspected the engine and determined it needed a new piston.

Pate continued to Sydney, while Doan and Rennie stayed at a fishing camp. Two days later, a Delta aircraft arrived with the replacement part. Repairs were completed, and they resumed their journey—but before reaching Sydney, they were ordered back to Ottawa.

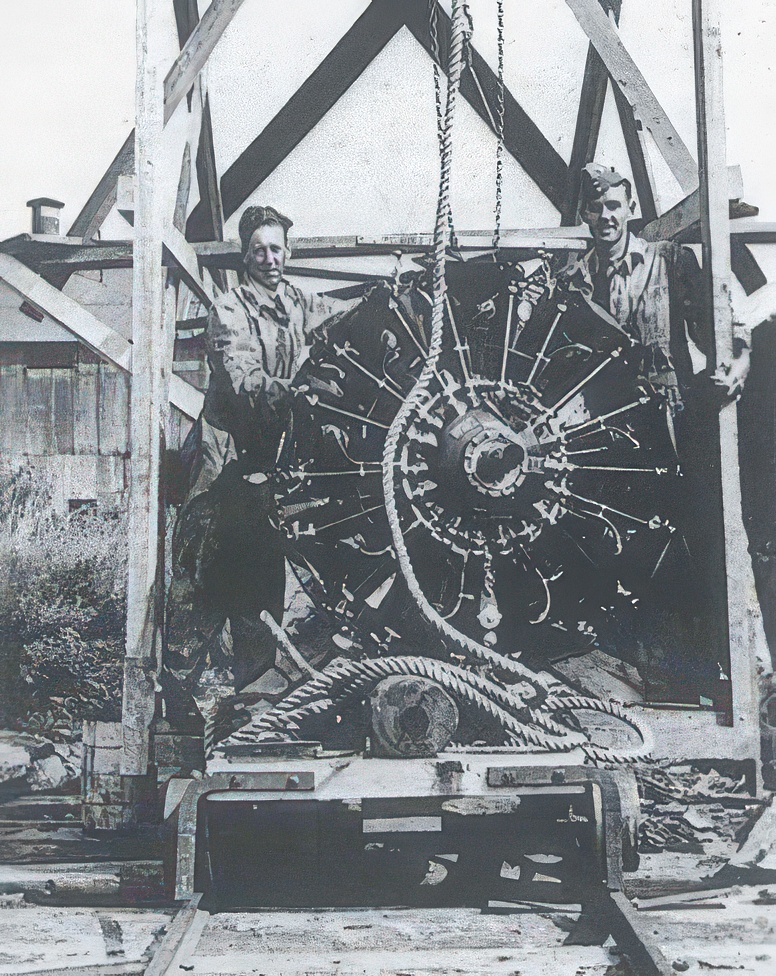

On their return flight, the engine failed again near Lac Megantic, on the Quebec-Maine border. Doan landed safely, but an inspection revealed the need for a complete engine replacement. In primitive conditions, the repairs took more than two weeks.

By the time they were ready to take off, war had been declared. Because the United States remained neutral, they could no longer fly across Maine. On September 14, they took off and headed north toward the St. Lawrence River.

Upon reaching Riviere du Loup, Doan turned east toward New Brunswick. Their aircraft was last seen south of Plaster Rock, sputtering as it flew. Then, they vanished.

When they failed to arrive in Shediac, the RCAF launched a search that lasted weeks. Reports trickled in, but none led to a breakthrough.

Nineteen years later, in July 1958, a forestry survey crew found the wreckage. The aircraft had plummeted nearly vertically, killing Doan and Rennie instantly. Though their mission had begun weeks before the war, they became Canada’s first RCAF casualties on home soil.