What Makes a Canadian?

Canada is not a particularly martial country. Its armed services have always been small, especially in consideration of the vast size of the country. But when it contributes, it punches way above its weight. The first foreign expedition was the British Empire’s call to arms for the Second Boer War in 1899-1902. Canada sent 8000 soldiers to South Africa. This was certainly a sizable effort considering Canada’s military strength at the end of the 1898 was less than 18,000 men. Canada also contributed in a large way during the Great War of 1914-1918. One in twelve Canadians served, and the casualty rate for those deployed overseas was terrible – 60,000 dead and 170,000 wounded (more than 50% of those who went overseas). That number does not include any Canadians who served in the British Army or Royal Navy or other allied services.

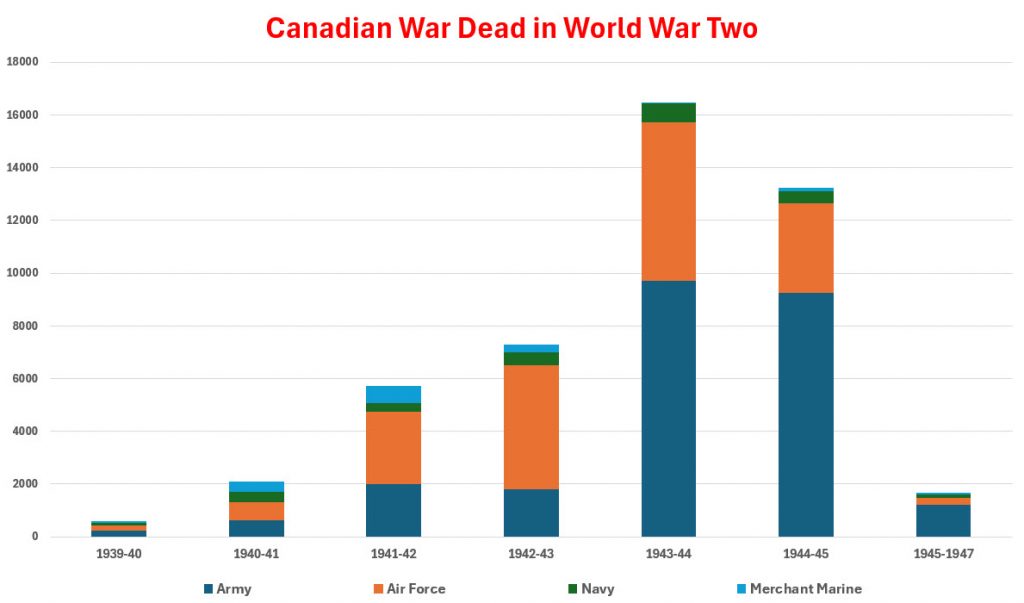

Its contribution in this new war was to be even larger. By the end of the 1945, Canada had the third largest navy in the world, the fourth largest air force and more than a million men and women (one in ten Canadians) were in uniform. Improvements in medical care and changes in tactics meant that the casualty rate was lower compared to the Great War, but still over 100,000 Canadians were counted among the casualties of war, including 44,000 Canadian servicemen and women who gave their lives.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) is tasked with maintaining the memory of 1.7 million Commonwealth fallen in nearly 23,000 cemeteries and memorials around the world from the First and Second World War. The CWGC initially identified some 45,000 of the dead as Canadians and passed that information onto the Canadian Government who now maintain a magnificent online Virtual War Memorial to the Canadian fallen.

Those who died serving in Canadian units are generally easily identified as a Canadian, but quite a number of these were Americans who volunteered prior to the US entry into the war in 1941. Over 800 of the 9000 American volunteers gave their lives.

The Canadians who died serving in non-Canadian units are a little more challenging to identify. The CWGC did so by finding “Canada” mentioned in the service record somewhere. However such a simple method of identification is also prone to some degree of over-generalization. It also meant that people who were born in Canada but had moved to the United Kingdom as a youngster would still be identified as Canadian. People who had been born in England, moved to Canada and then entered the service from Canada (returning to the “old country”) were still identified as Canadian.

Lieutenant JACK HOLME, British Army Intelligence Corps

At the turn of the 20th century, many Lancastrians (including my own grandparents, from a village near Liverpool) had an opportunity to emigrate to Canada with a promise of 160 acres of farmland. Richard Holme moved to Canada from his home in England to take up a ranching homestead in central Saskatchewan. He married Edith, an English lass who came to Canada a half dozen years later. Their son Jack was born on the ranch early in 1914.

Richard enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force and went to France where he was wounded in early 1916, at Messines in Belgium. His wound became infected with the results of a gas attack and both his legs were amputated. Edith soon set sail to return to England with Jack, now just two years old, to take care of her husband, Richard and they stayed in the UK.

Jack became a police inspector with the Metropolitan Police and when the Second War started, Jack signed up as an officer. His police background got him into the Intelligence Corps. He died in December 1940, in England when his car was crushed between two trucks and overturned while driving back home.

He was born in Canada, left when two and as far as we can tell, never came back to the land of his birth, but he is on the list of Canadians who died in the war.

As a postscript, his son Richard became a lawyer, ended up as a successful political figure in the United Kingdom, and died as Baron Holme of Cheltenham.

The connection to Canada may be sometimes as brief as that of Jack Holme, who left Canada at a young age, but the reverse is also true. Foreign nationals (primarily Americans) came to Canada at the outbreak of war for all the same reasons as Canadians who went to the United Kingdom: adventure, opportunity, a sense of duty. Their connection to Canada was often as long as it took to fill out the applications and undergo the training.

Pilot Officer BILLY FISKE, 601 Squadron Royal Air Force

Billy Fiske joined the RAF in 1940 from Montreal. When he was killed during the Battle of Britain, it was noted that he was Canadian and he was thus counted. Except he wasn’t.

Born in Chicago in 1911, Billy had been the captain of the US Olympic bobsled team in 1928 and 1932, winning gold medals. He studied economics at Cambridge University and was hired by a New York banking firm, Dillon. Reed and Company. Billy and another young banking friend bought some property in Aspen, Colorado and turned it into a ski resort, like they had seen in Europe during the Olympics.

He had been sent to the London offices of the bank in 1937 and while in England he married Rose Bingham, the Countess of Warwick. Shortly before the outbreak of war, he was recalled to New York, but he soon returned to England with a chum who was a member of the Royal Air Force Auxiliary. The US Neutrality Act meant that he could not join the services of a combatant, and the RAF was not actively recruiting Americans.

So, Billy wove a story about being a Canadian from Montreal and was accepted into the RAF Volunteer Reserve. He proceeded through training, was commissioned as Pilot Officer and in July 1940, was posted to join his friends at 601 Squadron, flying the Hurricane fighter from Tangmere. 601 Squadron, “the Millionaire’s Squadron” was so named because most of its hand-picked pilots were from wealthy and well-to-do backgrounds.

Billy’s squadron was scrambled to repel attacking Nazi bombers on 16 August 1940, and they acquitted themselves well, shooting down eight Stuka bombers that were attacking their base. One of the enemy gunners had a lucky shot through Fiske’s fuel tank and his plane caught fire. Rather than bail out, he nursed his wounded plane back to base and was pulled from it, in the middle of the air raid, just before it blew up.

His injuries were too great, though, and he died the next day in hospital. Olympian Billy Fiske had no link to Canada, but his records show that he came from Montreal to join the RAF.

It is more difficult to identify Canadians in the American services. The American Battlefield Monuments Commission, who look after the foreign war graves of the American fallen identify 64 Canadians as foreign nationals. But the American casualties are usually repatriated back home, and so the vast majority of them are not tended by the ABMC. The varied lists by state sometimes identify that a person “entered the service from Canada” just like they would have “entered the service from Oklahoma”. With cross-border traffic between Canada and the United States being quite open, we often get no indication of original nationality in their enlistment information. More often, however, we might find a hint in their next of kin information.

Yeoman 3rd Class FRED CARTER and

Seaman 1st Class GEORGE GUAY US Navy aboard USS Quincy

Fred Carter was born and raised in Woodstock, New Brunswick, 10 miles from the Maine border. In October 1940, at age 18, he went to Boston, Massachusetts and joined the United States Navy. He was assigned to the heavy cruiser USS Quincy and went aboard two months later.

They say “join the Navy and see the world” on the recruiting posters, and Fred certainly did. Over the next twelve months, prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor that brought the Americans into the war, Fred sailed the full length of the Atlantic Ocean from the Caribbean to Iceland, and down to South Africa, preserving US neutrality and protecting ships in convoy.

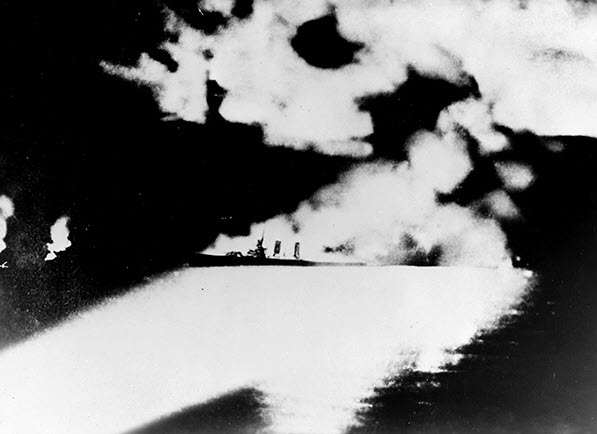

In the summer of 1942, the USS Quincy was sent to the Pacific Ocean and took part in the invasion of Guadalcanal. The Japanese fought back ferociously and the Quincy was sunk within 20 minutes of the first shots being fired.

Along with fellow Canadian George Guay of Levis, Quebec, Fred Carter is recorded as an American from Boston who gave his life for his country aboard the USS Quincy in the Battle of Savo Island, but in fact both are very Canadian.

The USS Quincy had a crew of over 800, but one does wonder if George and Fred knew each other well, and in fact knew that they were both Canadians.

Things are even more confusing for the Merchant Marine. Canada did not really have a merchant navy at the outset of the war, but by the end, there would be 12.000 sailors that would serve on the more than 400 ships flying the Canadian Flag. Canadians from every province also served in the merchant navies of other countries and shared the perils of the sea. Records at the beginning of the war are, however, sparse, and often incomplete.

Steward Dai Sheung, RMS Empress of Russia

Dai Sheung was a steward aboard the Canadian Pacific (CP Lines) ocean liner Empress of Russia serving Pacific Ocean routes. When he died in 1939, he was certainly in Canadian merchant service, but records of Chinese workers were not be kept too diligently at the time. How and why is lost to time.

For purposes of posts here, the identification of “a Canadian” will broadly fit one of three categories:

- Born in Canada, and served in the Army, Navy, Air Force or Merchant Marine of Canada or an ally,

- Not born in Canada, but came to Canada to join the Canadian military forces,

- Not born in Canada but had a life here prior to leaving to join a foreign (usually British or American) military force.

When one normally thinks of war dead, one imagines those shot down or sunk or shot on an invasion beach. War dead encompasses so much more, though. Amongst the fallen we will find people who were killed while training, or in accidents, or even from illnesses. Sometimes we can directly attribute their death to having been “on duty”. Sometimes, though, it is just a routine health issue or something that happens completely outside the call of duty that results in losing a life.

I have identified over 48,000 Canadians who gave their lives while in service, and periodically I run into a new one – a Canadian who served with a foreign military. There were 200,000 men and women who served in the Royal Canadian Navy and just over 2,500 gave their lives (1.3%). Of the 710,000 who served in the Canadian Army, more than 25,000 died (3.5 %) and the Royal Canadian Air Force lost 18,000 men and women (7%) from the 250,000 who served. In addition, the Merchant Marine are now (finally) recognized as having been a part of the contribution, and more than 1600 sailors died during the war in Merchant Marine service, out of 12,000 who served (13.3%)